As a Senior Fellow at the University of Washington School of Public Health, Dr. Sarah Andrea’s (@SarahBAndrea) research investigates strategies to mitigate gender, racial, and class-based inequities in health that originate early in the life course. I had the pleasure of meeting Sarah Andrea years ago, when I first started exploring the field of public health in her capacity as a doctoral student at Oregon Health & Sciences University. Since then, we have become great friends, and she has helped me through my professional development through her mentorship. In our first-ever Mentor Interview, I asked Dr. Andrea about her journey through public health, her supportive group of friends dubbed the EpiGirlGang, and her social media work starting the most fun and nerdy event ever: The EpiCookieChallenge! Please enjoy our spotlight on social epidemiologist, Dr. Sarah B. Andrea.

Can you introduce yourself? Where are you from, where have you been, and what has been the ‘thread’ in your research journey?

I am the youngest of six children, and the first and only person in my family to pursue a college education. I’m the first and only but not because I’m smarter or more hardworking than my siblings. I’m not. My resiliency is a product of love, support, encouragement, and multiple school-activists in positions of power who leveraged their privilege to remove barriers in my path..

It is not only my lived experience, but the knowledge acquired from rigorous research that I recognize early life experiences are powerful predictors of whether or not we finish high school, avoid becoming a teen parent, and go to college. It is because of my experience that I have a personal investment and insight into social determinants of health and understand many of the barriers that low-income people face. Because of this experience, I am a passionate mentor and advocate for students who are members of marginalized populations. My experience has shaped my research, which focuses on investigating strategies to mitigate or interrupt gender, racial, and class-based disparities in health throughout the life course.

Was your journey to epidemiology straightforward?

My journey has not been a straight shot by any stretch of the imagination! As a kid, I witnessed my family’s struggle, my siblings as the entered adulthood busting their ass and barely making ends meet. I knew I wanted to go to college, but I didn’t have a clear vision of what that would look like, what I would do after. My first of my six majors in undergrad (yup – changed five times!) was engineering because one of our few close family friends, who was a woman with a college degree, was an engineer. I finally graduated from undergrad with a degree in microbiology. My first step into research was made possible by one of my biggest schol-activists.

I had applied for a clerk position in a pathology lab, and Dr. Chapin at Rhode Island Hospital pulled my resume out of the pile and interview and hired me as her research assistant. She showed me a path I didn’t even know existed and gave me the tools that I would need to begin to walk it in the first place. She was the first mentor I’ve ever had, and I wouldn’t be here today without her.

I had never flown on a plane before until Dr. Chapin sent me to present a poster at a national conference. She knew the importance of this experience for me. She included me in the writing of several papers, even letting me be the first author on one – knowing that this was the currency that I would need if I decided to go on to graduate school. Simultaneously, she pushed me to sit for the exam that would certify me as a clinical microbiologist and to pursue licensure in the state of Rhode Island, so that I would have access to a more stable and well-paying job if the research road didn’t pan out.

I learned so much about myself and the kind of work and person I wanted to be right from my first research project. I was involved in a project to determine if highly sensitive molecular STI testing of non-invasive urine samples collected from children could be used in a court of law as evidence in abuse cases.

Skills wise, this project is where I got acquainted with the research process – from IRB submission to data collection, analysis, and writing. It involved chart review and abstraction, and I was charged with creating the abstraction tool. I can’t tell you how many times I had to go through the records over and over again because I realized at chart number 50 that we were missing a key variable or category. This was particularly difficult given the content that I was abstracting – these were interviews for all the children in the state of RI over four years who were being referred to our child safe clinic for reports of neglect or abuse. And these were extensive interviews with kids and their caretakers, with some challenging content.

Personally – reviewing the history of these children and how their lives were unfolding provided some acute insight for me about my family history. It was my first exposure to the literature on adverse childhood experiences, and it also highlighted the vulnerability of childhood and the role of health providers, teachers, community members, family, and friends as gatekeepers who can be a source of advocacy or hindrance. And projects like this catalyzed my fascination with social and political forces as levers to promote health equity.

It’s been a decade, and I’ve worked in a variety of research settings since then – but this fascination is what continues to drive me.

Undertaking a Ph.D. is undoubtedly a huge decision. What were the drivers that made you want to become Dr. Andrea? How were your expectations different than reality? What was your favorite part of your doctoral years?

Keeping in mind that I never thought I would go on for a master’s degree, never mind a Ph.D. This was another situation where I didn’t know until I knew! During my masters, I was working full time as an RA and I took on TAing to further supplement my income. I found that I liked mentoring, that I enjoyed being on other people’s research teams. Still, I also had questions that I wanted to have the ability to investigate, that I wanted to have a firmer grasp on the tools I would need to go about conducting my research and that I wanted to be in a position where I could help break down barriers for folks the way that others have done for me. I think with the right research team, you can still be supported to conduct somewhat independent research at the masters or even bachelor’s level, but it’s currently still pretty hierarchical.

I didn’t know what to expect – I had no framework. I didn’t think it would be a whole lot different from doing my masters while working full time as an RA – classes plus research, right? But it’s different. There is so much learning and personal growth. I’m simultaneously delighted and proud of myself for doing it, and glad I will never have to do it again!

I formed incredibly strong bonds with my cohort, my #EpiGirlGang. We were a lifeline for each other through the program. We continue to have a very active group chat where we support each other despite being hundreds or thousands of miles away from each other.

Why did you develop an interest in epidemiology and specifically, social epidemiology?

You know, I didn’t realize what epidemiology was until about a year into my first research job. There I learned the things I like most about the work I was doing was epidemiology!

I love the detective work of it, the methods, and thinking through how we can get to the answer we are looking for given the complexities of life, the complexities of the data source, and more. I also really identify with this idea of consequential epidemiology, and I gravitated towards social because no matter what health outcome I was evaluating, the closer I looked, the more I could see the underlying social and political forces.

4. In my work, I’ve found there’s a lot of insight that I gain from studying exposures which affect me (i.e., transgender status, being queer, etc.). At the same time, this can make the work feel more ‘close to home’ and create additional stressors because, you know, we live some of the things we study. Many of us in public health are ‘wounded healers’ in some way. How does your background tie into the research you do? How do you balance this insight with potential stress?

Sure my lived experience informs the lens through which I see the world and shapes the questions I’m inclined to ask. And that’s one of the reasons why we should all be fighting for a more inclusive and diverse public health workforce. From a social justice perspective, the efforts of my scholactivists have improved my personal quality of life but also from a public health perspective, I’m in a position now where I can ask questions informed by my lived experience that people that grew up under different circumstances or what have you didn’t know to ask. If we don’t ask the right questions, we’ll never get the correct answers.

Yes, sometimes taking the deep dive into some of the literature surrounding topics that I’m intimately aware of through personal experience can be stressful. More often than not, I have found the plunge into the literature surrounding classism, sexism, and more as structural determinants of health to be very validating.

#epicookiechallenge was something you created last December on Twitter. Many people submitted epidemiology-themed cookies of DAGs, graphs, and causal loops, and you created a poll to collect votes on the winner this January. Can you tell us about the #epicookiechallenge, and what inspired you to create his challenge?

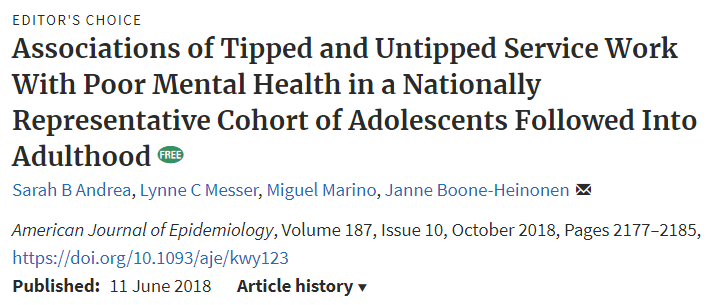

To give credit where credit is due, a week before the holiday break Dr. Dominique Heinke (@Epi_D_Nique on twitter) had briefly tweeted that she wanted to take a crack at doing a little #scicomm of her research area via a cookie. Knowing how into food-related things and #scicomm the epidemiology community is on twitter (#epitwitter) I sort of casually proposed that we have an #EpiCookieChallenge where folks take a crack at increasing the accessibility of epidemiology concepts or their research via cookie and that the American Journal of Epidemiology should offer a prize for the winner. AJE’s social media guru Dr. Ellie Murray (@EpiEllie on twitter) – who is also the cohost of AJE’s new podcast “Casual Inference” – took an interest, and I suggested the winner should have the opportunity to explain the meaning behind their cookie on a future episode. This suggestion was very well received and they recorded an episode with the winner, so be sure to check out Episode 6.

** If you’re interested in interviewing one of your mentors to submit to a publication, get in touch with us! **

- Series 4– Public Health Solidarity - September 15, 2020

- Inequity, Domination, and Liberation during COVID-19 - September 15, 2020

- Archive – The Palate, Nutrition and Public Health - July 6, 2020