The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot gives light to the story of Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman who died of cervical cancer, but not before doctors took samples of her cells without her knowledge. Medical researchers would soon find that these cells were immortal, something never before seen in humans, leading the way to the study of biological science as we know it today. This story was one of betrayal from the Johns Hopkins hospital, and heartbreak over the loss of someone special. Skloot, who is an experienced science writer, touches upon some significant concepts throughout the book, ranging from the mistreatment of Blacks and minorities as research tools for medicine, to the lack of knowledge the Lacks family had towards mental health and their well-being.

Henrietta Lacks was born around the time of the Jazz Age when Jim Crow laws were still in practice, and segregation was the norm. This book was written in a time-lined fashion from before Henrietta was born up until the death of her daughter Deborah in 2009. Chapter to chapter, Skloot switches from following Henrietta’s story to following the stories of the different researchers and doctors involved. Not only did she keep the voices of the various characters alive in the text, but Skloot paints an unbiased picture of what happened, allowing the reader to develop their own opinions about the issue.

Henrietta Lacks died around the same time that the Tuskegee syphilis experiments were being conducted, the civil rights movement was underway, and the Black Panther movement was making a stronger appearance. All of these movements were significant because they were reactions to prevalent racism that has far outlived Henrietta. Throughout her illness, it was reported that Henrietta complained to her providers of the pain, only to be dismissed or given more doses of radiation. Dismissing the suffering of African American women is not something of the past; it is still present today. For example, prominent figures like Beyoncé and Serena Williams have opened up about the difficulties they faced during their pregnancies due to healthcare providers not believing they were in pain. It is systemic racism playing out time and time again; minority pain is not taken seriously, often resulting in relative or extremely detrimental results.

This lack of sympathy white doctors had towards taking Henrietta’s cells brought up an important question of morals and ethics within the medical field, as it relates to minorities. When the misconduct of Johns Hopkins was discovered, the story about a Black woman wrongfully researched on for the benefit of the white man spread like wildfire. How could the doctors take her cells without anyone knowing? Why was her family not informed or given any profit from the money that was made from that research? This also makes one wonder that if Henrietta had been born White and not Black, would this incident have taken place the way that it did? It’s important to note that HIPAA – a law passed in 1996 to establish security standards to protect human health information – was not enacted at this time, so it was legally permissible for doctors to share patient information without consequences. Skloot addressed this by contemplating whether legality equates with rightness when dealing with patient privacy.

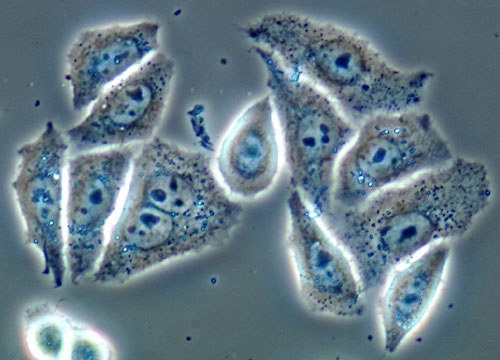

Patient privacy concerns were manifest in the Lacks’ discomfort about their family information being out in the open. They had many family secrets that would hurt the family name if the public discovered it. Rape, abuse, and mental illness left many Lacks members with unaddressed trauma. In many minority communities, these topics are taboo and are often shoved under the rug, which was what the Lacks family did. The HeLa cells – the immortal cell line created from Henrietta’s stolen cells – were named for her and were just about the only credit she got. Without the family, there is no Henrietta, and without Henrietta, there is no HeLa. Skloot touches upon this point several times as she recounts her conversations with the Lacks family and is clear from her research into the family and story she had already collected.

Skloot ends the book reminiscing about an interview she watched featuring Deborah talking about her mother. Given their Christian beliefs, Deborah had a firm conviction that God chose Henrietta to be the one with immortal cells because of her good character and love for people. Many members of the Lacks family shared this optimism; even though the Johns Hopkins community betrayed them, they felt that God was taking care of their mother. Deborah noted in the book, “I really believe she’s up in heaven, and she’s doin okay, because she did enough suffering for everyone down here.” This powerful statement not only confirmed the forgiveness of the Lacks family towards the researchers who wronged them, but summed up who Henrietta Lacks was as a person.

Overall, this was an insightful book addressing a controversial issue in the medical world. This is a must-read for those in the science field and highly encouraged for anyone curious about the implications that morals have on a person’s well-being and reputation. The story of HeLa cells is still relevant; a big public medical institution stole the cells of an unaware poor Black woman and left her to die for their research benefit. There are still severe racial and social inequities present today. Some degree of this story, whether exaggerated or not, has circulated mainstream society and is one that should not be forgotten.

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks – Book Review - January 14, 2020

- Why Public Health? From Personal Experience to Proudest Achievement - August 20, 2019

Pingback: Intervene Upstream Issue 2: Creativity & Social Work » Intervene Upstream, the online peer-reviewed public health publication for graduate students