Introduction to Sex Discourse in the United States

In the United States (US), 95% of the population has sex before marriage.1 On average, young people have sex for the first time at age 17 and get married in their late 20s, and during this interim period, they are at increased risk for unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1

That said, it is crucial for young people to obtain knowledge and skills with which they can protect themselves and their partners. Formal sex education has been utilized for this purpose for decades; however, the most widely funded approaches have not been those proven effective. Over two billion federal dollars have been spent on abstinence education since 1981, but these pedagogies have since been proven to be ineffective.234567

Why does the federal government continue to fund ineffective sex education programming? Adherence to certain sexuality discourses and ideologies could be an explanation. This piece serves three purposes: (1) to describe sexuality discourses and how they affect governmental support for programming, (2) to describe in brief the history of federal funding for sex education programming and (3) to caution against the prioritization of ideology over evidence.

Conservative Sexuality Discourse

Much of conservative sexuality discourse centers on control and suppression of sexual urges outside of procreative sex.8 This discourse often emphasizes biological essentialism, describing the “correct” functioning of reproductive bodies, including strict roles and attributes of male and female bodies and sex that leads to the reproduction of life.8 Conservative sexuality discourse contains elements of physical hygiene and sexual morality, wherein notions of unclean genitals and corrupt bodies are used to discourage sex outside of marriage.8 There is a desire to preserve children’s youthful innocence and a fear that exposure to matters of sexuality will encourage sexual exploration among children.8 These ideas have led to minimalistic, often misleading, sex education. Conservative sexuality discourse is the foundation of abstinence education, which communicates an expectation of complete sexual avoidance for adolescents before marriage.98

Liberal Sexuality Discourse

Liberal discourses embrace a fluid conceptualization of sexuality imbued with individual sexual rights.8 The existence of personal choice, negotiation, reciprocity, and pleasure in sexual experiences is vital, along with the elimination of notions of uncleanliness and shame.8 Liberal sexuality discourse has led to the development of sex education that provides information about a wide range of sexuality topics. Medically accurate information about contraceptive methods, STI and HIV prevention, and other topics is included. The purpose of sex education is to promote the progressive development of sexuality and decision-making capacities of students using evidence-based pedagogies through the facilitation of knowledge- and skill-building.8 Comprehensive approaches to sex education were developed to combat the lack of medically accurate information being shared with students8

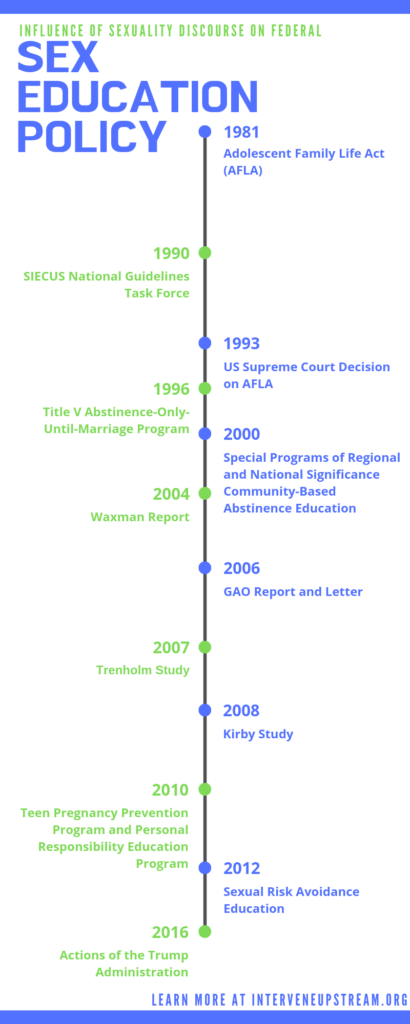

A Timeline of Sex Education Discourse from Reagan to Trump

Conservative and liberal sexuality discourses have guided federal support for various sex education policies since 1981. Below listed are significant acts and programs and court decisions from the Reagan-era to the current era with brief background descriptions.

1981 – Adolescent Family Life Act

In 1981, Republican Senators Jeremiah Denton (R-AL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT), called for morality- and family-values-based approaches to prevention of adolescent sexual activity and unintended pregnancy.1011) They sponsored the Adolescent Family Life Act (AFLA), which would fund programs promoting “self-discipline and other prudent approaches,”12 to combat adolescent sexual activity.10 Without Congressional hearings or floor votes, Sens. Denton and Hatch included this legislation in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 as Title XX of the Public Service Act.10 The program’s early grantees were almost exclusively religious and conservative groups, many of which created and used fear-based curricula to enforce abstinence, sometimes negating efficacy of contraception and STI prevention strategies.10

1990 – SIECUS National Guidelines Task Force

The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) convened the National Guidelines Task Force in 1990.3 The panel of experts created the Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexuality Education – Kindergarten – 12th Grade, a framework to guide the creation of effective curricula and the evaluation of existing programs3 Updated editions were published in 1996 and 2004.3 According to the guidelines, comprehensive sex education promotes sexual health by providing accurate information about human sexuality; facilitating development of healthy attitudes, values, insights, and critical thinking skills; facilitating development of communication, decision-making, assertiveness, and peer-refusal skills; and encouraging adolescents to make responsible choices.3

1993 – US Supreme Court Decision on AFLA

Questions of constitutionality lead the American Civil Liberties Union to challenge the AFLA in court, arguing that it violated the principle of separation of church and state.310 In 1993, the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) held that federally funded programs must eliminate direct religious references; however, by this time, some of the largest grantee programs had already been adopted into public schools.3.To comply with the SCOTUS ruling, the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention (OAPP) conducted rigorous reviews of AFLA programs, screening for religious and medically inaccurate material.10 Federal funding was available through the AFLA for abstinence education until 2010; during its 29-year implementation period, AFLA received more than $200 million.13

1996 – Title V Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Program

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 contained a provision to create a block grant program to fund abstinence-only-until-marriage education (AOUM).14 Like the AFLA, this provision was included in the law without legislative or public debate13 Each year beginning in FY 1998, $50 million would be allocated to Title V Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Block Grant Program.14 States that accepted Title V grant money were required to match every four federal dollars with three state dollars and distribute funds to schools and community organizations.9 AOUM programs funded through Title V followed the A-H definition of abstinence education.9313 According to this definition, AOUM programs were required to communicate an expectation of abstinence from sexual activity outside marriage; exclusively emphasize the social, psychological, and health benefits of abstinence until marriage; and stress the potential psychological and physical harms of engaging in sexual activity outside of marriage.93 The A-H definition of abstinence education was also retroactively applied to AFLA programs.13 Title V-funded programs were not permitted to include discussion of contraceptive methods, unless to emphasize their failure rates.13 Title V funding, originally authorized for five years, was continually extended by the Bush Administration until it was allowed to expire in 2009.13 Conservative legislators made several attempts to revive the program and successfully inserted a provision for funding into the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed under the Obama Administration in 2010; it continues to be funded.13.

2000 – Special Programs of Regional and National Significance Community-Based Abstinence Education

In 2000, the federal government created the Special Programs of Regional and National Significance Community-Based Abstinence Education (CBAE) program, which awarded grants directly to state and local organizations.13 Grantees were required to adhere to the A-H definition of abstinence education.13 CBAE funding increased from $20 million in 2001 to $113 million in 2006; that level of funding remained until the budget was reduced to $99 million in 2009.13 In 2010, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which eliminated all discretionary funding for CBAE.13

2004 – Waxman Report

Representative Henry Waxman (D-CA) ordered an evaluation of content in the most widely-used abstinence education curricula; The Content of Federally Funded Abstinence-Only Education Programs, popularly known as the Waxman Report, was published in December 2004.7 The report found that over 80 percent of abstinence education curricula contained false, misleading, or distorted information: failure rates of contraceptives and risks of abortion procedures were found to be erroneously inflated, religion and science were conflated, gender stereotypes were treated as scientifically factual and curricula contained scientific errors.7 Two-thirds of programs funded through CBAE, the largest source of federal abstinence education funding at that time, utilized misleading curricula.7.

2006 – GAO Report and Letter

In response to the Waxman Report, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) released a report in 2006.3 The GAO found that many federally funded abstinence education programs were not reviewed for accuracy prior to funding and implementation; GAO also sent a letter to the HHS Secretary recommending that abstinence education curricula comply with legislation requiring that STI prevention education be medically accurate [Section 317(c)(2) of the Public Health Service Act]3615

2007 – Trenholm Study

In 2007, the final report from an experiment on the impacts of four Title V AOUM programs, popularly called the Trenholm Study, was submitted to HHS5. The four programs evaluated included various implementation strategies and curricula, representing the range of A-H abstinence education programming funded through Title V5 Investigators concluded that none of the programs evaluated were effective in delaying sex, reducing unprotected sex, or reducing number of sexual partners; additionally, adolescents exposed to the Title V programs were less likely to believe that condoms reduce the risk of STIs.5

2008 – Kirby Study

Douglas Kirby conducted a rigorous review of 56 studies of sex education program efficacy and published findings in 2007 and 2008.4 These studies evaluated nine abstinence education programs and 48 comprehensive education programs; far fewer studies on abstinence education program efficacy meet the inclusion criteria for this review, indicating that these programs are not as scrupulously evaluated as are comprehensive programs.4 The review revealed that comprehensive programs were significantly more likely to elicit the desired behavioral effects in adolescents than abstinence programs: delayed initiation of sex, reduced frequency of sex, reduced number of sexual partners, increased condom use, increased contraceptive use and reduced sexual risk-taking.4 With this, Kirby concluded this evidence did not justify the widespread implementation of abstinence education programs and that application of comprehensive education programs show strong positive effects.

2010 – Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program and Personal Responsibility Education Program

In response to the growing body of evidence supporting the efficacy of comprehensive sex education, the Obama Administration transferred federal funds from CBAE programs and budgeted $190 million for new evidence-based approaches in 2010.316 The Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP; allocated $110 million) is a two-tiered program designed to support the creation and implementation of evidence-based comprehensive sex education programs.17 Tier 1, allocated $75 million, provides support to programs replicating methods proven effective through rigorous evaluation in reducing adolescent pregnancy, delaying sexual activity, increasing contraceptive use, or reducing incidence of STIs.17 Tier 2 provides at least $25 million in funding for research and demonstration of new sex education and adolescent pregnancy prevention methods.17 Two cohorts of grantees have received funding thus far; the first cohort received funding from 2010 to 2015, and the second received funding in 2015. As previously mentioned, the Trump Administration unsuccessfully attempted to disrupt grantee funding in 2018.9 However, the Trump Administration was successful in altering guidelines for future TPPP grantees, mandating that they replicate an abstinence education program, rather than a comprehensive sex education program9 President Trump’s FY 2020 budget proposal did not fund the TPPP; however, on May 8, 2019, the House Appropriations Committee passed its FY 2020 House Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies bill, which included $110 million – a $9 million increase – for TPPP.18

The Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP) was also created in 2010 to increase the number of evidence-based programs in use.3Three types of grants are awarded through PREP: formula grants provided to states that replicate evidence-based programs, competitive grants to public and private entities testing innovative approaches, and tribal grants to support culturally appropriate adolescent pregnancy prevention methods.19 PREP-funded programs must educate adolescents on abstinence, contraception, and at least three of the following “adulthood preparation subject areas: healthy relationships, positive adolescent development, financial literacy, parent-child communication skills, education and employment preparation skills, and healthy life skills.19

2012 – Sexual Risk Avoidance Education

The newest federal abstinence education funding source is the Sexual Risk Avoidance Education (SRAE) program, established in 2012.9 Like the CBAE program, SRAE bypasses state governments to directly fund community organizations.9 It initially required grantees to adhere to the A-H definition of abstinence education, but has since dropped the requirement; programs must still teach youth to abstain from sexual activity before marriage.9

2016 – Actions of the Trump Administration

Trump Administration officials attempted to prematurely terminate funding of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP), a comprehensive sex education program that will be discussed later in this paper.9 The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sent notice to grantees that their funding would end in 2018, two years early, due to lack of exhibited program efficacy9 In four lawsuits, grantees argued that their grants were wrongfully terminated; federal judges ruled in favor of the grantees in each case and their programs are allowed to continue until the end of the grant cycle in 2020.9 The Trump Administration altered guidelines for new TPPP grantees. Grantees are now required to replicate one of two abstinence programs; originally, they could replicate one of 44 evidence-based programs.9 Additionally, Congress passed the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which increased funding for SRAE programs by $10 million.9

Conclusions

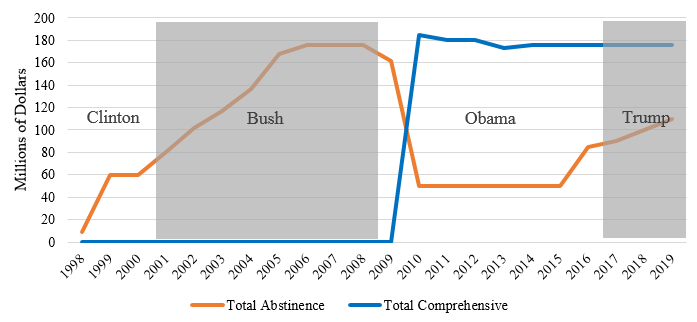

Evidently, prominent sexuality discourses drive federal funding for sex education programs. Since the beginning of federal funding efforts for sex education, conservative administrations increased funding to abstinence education programs, which have been shown time and again to be ineffective.13204567. The Obama Administration greatly reduced support for abstinence education programs in favor of evidence-based comprehensive programs. It is worth noting that in 2016, funding for abstinence education programs was increased from $50 to $85 million, despite attempts by President Obama to eliminate funding for these programs.20 This brings to light a common issue in the US government: Executive and legislative bodies often have opposing priorities, influencing federal funding priorities. The figure below exhibits the separate funding streams for abstinence and comprehensive programs from the fiscal year 1998 to the fiscal year 2019.

Federal Funding for Abstinence and Comprehensive Programs

by Fiscal Year, 1998-2019 Sources: SIECUS 20182. Fernandes-Alcantara21, 2018.

Sources: SIECUS 20182. Fernandes-Alcantara21, 2018.

This change indicates that officials in the Obama Administration were responsive to mounting evidence supporting comprehensive sex education pedagogies. They opted for methods that were proven to reduce adolescent pregnancy and prevent STIs. The Trump Administration has not followed suit, instead doubling funding for Title V and SRAE programs since taking office in 2017 and attempting to disrupt funding for TPPP grantees.29. These actions make clear this Administration’s adherence to conservative sexuality discourse and prioritization of ideology over scientific evidence.1 These actions reduce capacities for young people to have safe, happy and healthy sexual experiences. It is vital to re-prioritize evidence-based methods of knowledge- and skill-building to promote adolescent development.

- Influence of Sexuality Discourse on Federal Sex Education Policy - August 24, 2019

- Donovan, M. K. (2017). The Looming Threat to Sex Education: A Resurgence of Federal Funding for Abstinence-Only Programs? Guttmacher Policy Review, 20. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2017/03/looming-threat-sex-education-resurgence-federal-funding-abstinence-only-programs [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- SIECUS – Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. (2018). Dedicated Federal Abstience-Only-Until-Marriage Programs Funding by Fiscal Year (FY), 1982-2019. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- PPFA – Planned Parenthood Federation of America. (2016). History of Sex Education in the US. Retrieved from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/uploads/filer_public/da/67/da67fd5d-631d-438a-85e8-a446d90fd1e3/20170209_sexed_d04_1.pdf [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Kirby, D. B. (2008). The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 5(18), 18–27. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Trenholm, C., Devaney, B., Fortson, K., Quay, L., Wheeler, J., & Clark, M. for Mathematic Policy research Inc. (2007). Impacts of Four Title V, Section 510 Abstinence Education Programs – Final Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- GAO – Government Accountability Office. (2006a). Abstinence education: Efforts to Assess the Accuracy and Effectiveness of Federally Funded Programs. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Waxman, Henry. (2004). The Content of Federally Funded Abstinence-Only Programs. Washington, DC: US House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jones, T. (2011). A Sexuality Education Discourses Framework: Conservative, Liberal, Critical, and Postmodern. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 6, 133–175 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- KFF – Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). Abstinence Education Programs: Definition, Funding, and Impact on Teen Sexual Behavior. Women’s Health Policy. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/abstinence-education-programs-definition-funding-and-impact-on-teen-sexual-behavior/ [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Saul, R. (1998). Whatever Happened to the Adolescent Family Life Act? Guttmacher Policy Review, 1(2). Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/1998/04/whatever-happened-adolescent-family-life-act [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981. 42 USC §§ 300z. (1981 [↩]

- Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981. 42 USC §§ 300z. (1981). [↩]

- SIECUS – Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. (n.d.). A History of Federal Funding for Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Programs. Retrieved from https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/4-A-Brief-History-of-AOUM-Funding.pdf [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- HHS – US Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/personal-responsibility-and-work-opportunity-reconciliation-act-1996 [↩] [↩]

- GAO – Government Accountability Office. (2006b). Abstinence Education: Applicability of Section 317P of the Public Health Service Act. Letter to Honorable Michael O. Leavitt, Secretary of Health and Human Services [↩]

- Kappeler, E. M. & Feldman, A. (2014). Historical context for the creation of the Office of Adolescent Health and the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, S3-S9. [↩]

- Kappeler, E. M. & Feldman, A. (2014). Historical context for the creation of the Office of Adolescent Health and the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, S3-S9 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Power to Decide. (n.d.). Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) Program. Retrieved from https://powertodecide.org/teen-pregnancy-prevention-tpp-program [↩]

- Youth.gov. (n.d.). Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative. Retrieved June 12, 2019, from https://youth.gov/evidence-innovation/investing-evidence/teen-pregnancy-prevention-initiative [↩] [↩]

- Hall, K. S., Sales, J. M., Komro, K. A., & Santelli, J. (2016). The State of Sex Education in the United States. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 58(6), 595–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.032 [↩] [↩]

- Fernandes-Alcantara, A. L. (2018). Teen Pregnancy: Federal Prevention Programs. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. [↩]

Pingback: Introducing Intervene Upstream: 2019 Inaugural Release » Intervene Upstream, the online peer-reviewed public health publication for graduate students

Alicia – congrats on being one of our two most-read articles since the launch! We are going to feature this in our newsletter! 🙂