A Book Review of Hector Abad Faciolince’s El Olvido Que Seremos

In El Olvido Que Seremos, Hector Abad Faciolince celebrates the life of his father, a leading physician, population health scientist, and human rights activists in Medellín, Colombia, who was assassinated during the armed conflict in Colombia in the second half of the twentieth century. The beautiful prose springs from the pages of the book to envelope your heart and inspire the full spectrum of human emotions in a real, raw way.

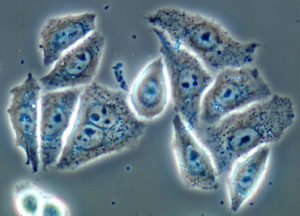

This authentic account of a son’s love for his father is also an informative and profound reflection on public health as a transdisciplinary academic field and in a global context. Reflecting on his father’s medical training and passion for epidemiology and non-clinical medicine, Abad Faciolince writes, “La epidemiología ha salvado más vidas que todas las terapéuticas”: Epidemiology has saved more lives than all treatments/therapeutics. He shares how his father believed in experiential education and propagated the central role that social determinants of health play in health outcomes by taking his students to vulnerable neighborhoods in Medellín.

Through this powerful and personal narrative, Abad Faciolince affirms that medicine must be understood in the most inclusive and expansive manner possible, to develop sustainable solutions that address upstream risk factors that may not fall into the classical, clinical understanding of medicine. He suggests that some of these less traditional approaches must take priority. “La sangre de la peor de las enfermedades padecidas por el hombre: la violencia”: the blood of the worst disease suffered by man is violence. Recounting the endless assassinations of community and academic leaders and friends from his perspective as a young boy and a timid man, he elucidates the systematic fear, violence, and repression of expression that took place in Colombia during this time. In fact, when reflecting on the armed conflict in Colombia, he writes that violence is born from the feeling of inequality. (“Esta violencia nace del sentimiento dedesigualidad.”) He continues to say that human rights are the most urgent medical fight of the moment: “Los derechos humanos … [son] la lucha médica más urgente de eso momento en Colombia.”

Abad Faciolince moves the conversation even farther upstream than social determinants of health. He declares, “La ignorancia … [es] la fuente de todos los males que agobian el mundo,” or that ignorance is the source of all the evils that plague the world. In other words, and echoing lessons learned from Colombian author Ángel Rama’s La Ciudad Letrada, he asserts that fighting ignorance, perhaps through education and expression, is what transforms and advances society. This idea is repeated throughout the narrative. Toward the end of the book, Abad Faciolince recounts how an assassin publicly stated that he was “knocking out the brains” of his victims (“anularles el cerebro). While intended as a euphemism for death, Abad Faciolince poignantly notes how the ceaseless violence did exactly what the assassin colorfully described: it literally voided the brains from society. It instilled fear in the public and suppressed freedom of expression by community leaders. Reasonable dialogue and relentless respect for the other had been replaced by fascist repression.

El Olvido Que Seremos offers significant insight into both leadership and humanity. Through the pure reflections of a boy admiring his father, Abad Faciolince highlights qualities that he admires in his father and others while candidly and humbly admitting that they may never be qualities he will possess. In fact, an important motif in this book is about defining our purpose – after all, the title of the book roughly translates to “we will be forgotten.” “La fijación de metas distingue a unos hombres a otros”: goal setting distinguishes some men from others. Throughout the entire book, Abad Faciolince reiterates his father’s selflessness and concern for others and admires the example his father set. “Hay una fuerza interior que los impele a trabajar a favor de los que necesitan su ayuda. … Esa lucha le da significado a vida.” There is an inner force that impels one to work for those who need his or her help. … That fight gives meaning to life. On the most basic level, the author reminds us that our purpose as humans is to help others. This is the fuel for the fire that we call life.

Finally, there is an implicit lesson in this masterpiece that cannot go unnoticed: The power of storytelling. At one point, Abad Faciolince writes, “No digo de vengar su muerte, pero sí, al menos, de contarla”: I do not say this to avenge his death, but yes, at least, to tell of it. Words are not supposed to incite more violence, but are used to help us remember. He reflects, that words transmit, in part, our ideas, our memories, and our thoughts. (“Las palabras transmiten en parte nuestras ideas, nuestros recuerdos, y nuestros pensamientos.”) Words, his preferred medium for expression, accomplish the following: “este olvido que seremos puede postergarse por un instante más”: we can postpone the forgotten that we will become for a moment more. On a personal level, the author does not want to forget the beautiful life of his father. He wants to celebrate his father and his legacy. On a communal level, storytelling allows us to remember. Colombia Professor Yosef Yerushalmi instructed that to forget is the true cardinal sin. In a vulnerable and genuine account, Abad Faciolince codifies his father’s memory and legacy in this book so that it will not be forgotten. By doing so, he re-inserts himself into his father’s living legacy. He helps to disseminate and translate the lessons from his father’s life, tragically ended early, making him an active agent in his father’s mission to help others and fight for human rights.

- A New Year, A New Needed Perspective - November 17, 2022

- Navigating the Line Between Discomfort and Uncomfort: Exploring Cultural Immersion - November 2, 2022

- Locating Eckhart Tolle’s “A New Earth” Within Current Public Health Epistemology: A Book Review - October 12, 2022