Content warning: mental illness, image of gun, reference to suicide. Note: Images are redacted for de-identification purposes.

Addressing Mental Illness as a College Student

The first time I set up a therapy appointment, I didn’t go.

It wasn’t because I changed my mind. I had already spent a few months in various stages of denial about whether or not it was the right decision. After coming to the conclusion that it might not be normal to feel anxious 24/7 and spend all my free time in bed, I figured it couldn’t hurt. I called my university’s counseling center and was told that the first available opening was in six weeks. Not knowing about any other options, I reluctantly chose the month-and-a-half wait.

The morning I was supposed to go in, my therapist called me to cancel the appointment. She did not tell me why. She did not reschedule. She did not provide off-campus resources. I visited the counseling center’s website, where I found that half the links took me to error pages or contained outdated information. I emailed every staff person whose information I could find, asking (read: begging) for guidance. Eventually, one staff member gave me a list of providers who took my insurance, a resource that wasn’t on the university’s website and that none of my friends or classmates who had contacted the counseling center had ever received. Much later, I found out that my experience was not at all unique.

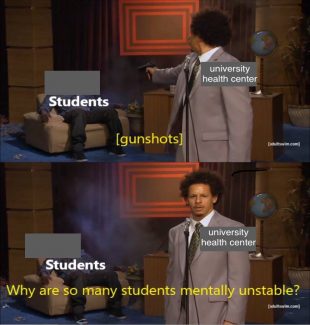

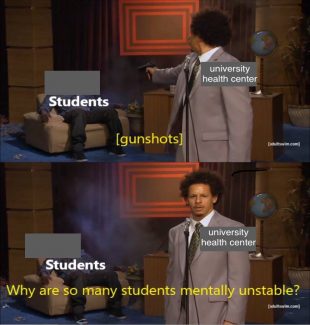

It is probably unsurprising that the mental health services at my university were a running joke within the student community. Very few students were receiving any kind of treatment despite high rates of mental health issues, particularly depression and anxiety. Frequently, students shared memes on social media about our university’s lack of resources. We students shared a feeling that the only way to cope with what appeared to be a widespread mental health crisis was to transform our symptoms of anxiety and depression into something relatable. Misery loves company.

Image created by author

I have no doubt that the therapists at my university are qualified and competent. The issues that my peers and I experienced had less to do with individual providers or their level of expertise than the larger system under which they are forced to operate. The crux of the issue is that mental health in any community cannot flourish until structural changes take place that target accessibility and attitudes towards treatment.

A Universal Experience

When I first started studying psychology, I wanted to be a therapist. I saw firsthand how necessary it is to address one’s own mental health to feel successful and fulfilled in life. However, I eventually became more interested in understanding how the broken healthcare system and a lack of treatment accessibility can be just as damaging as any illness. The process of finding a therapist should not be a source of overwhelming stress, as it was for me and countless other students. People who struggle with mental illness should not have to risk exacerbating their own symptoms to find treatment. If someone is already feeling discouraged and vulnerable, the act of cold calling a provider or navigating a website with links that lead to dead ends might be stressful and confusing enough to completely discourage them from continuing to pursue help.

Once I began to discuss my mental health with others, it seemed as though every person I met had a similar experience. One friend’s symptoms of anxiety were downplayed by faculty and brushed off as “just stress,” despite the person feeling too anxious to leave their dorm room to attend classes. A classmate confided in me that when their symptoms of severe depression were “concerning” to their professors, instead of providing support and resources, they were pushed by their professor to go on medical leave without receiving any guidance on how to return. Many students reported being unable to get in touch with clinical staff to get refills on their medications and had to go without them, which led to worsened symptoms or withdrawal. We considered a four-week wait time for a single therapy appointment to be short. Taken as a whole, all of these problems created a climate where mental health symptoms were overlooked, ignored, and belittled. Over time, the stigma against mental health issues took a toll on both our mental and physical health.

As a result of this unhealthy climate, addressing my own symptoms of depression and anxiety was difficult for a long time. My social life and academic performance were suffering, but the idea of pursuing treatment made me feel as though I was taking resources away from someone else who needed them more. I experienced something I call reverse imposter syndrome. Instead of doubting my own successes and accomplishments, which is what is generally associated with this term, I felt that saying “I have an illness” would be seen as somehow fraudulent. In my mind, my symptoms weren’t serious enough to be worthy of evaluation, let alone treatment, despite knowing that I was struggling. I was ashamed. It was a point of pride that I always made sure to check in on my friends and point them towards resources when they were struggling. I joined an advocacy group on campus that worked towards increasing the accessibility of health services. I made it loud and clear to everyone I knew that I was an advocate for treatment, and I still managed to fall prey to internalized stigma. I wondered how common of an experience this was.

There is No Health Without Mental Health

Mental illness is one of the most prevalent health issues in the world. Globally, it is estimated that nearly 1 billion individuals have either a mental or substance use disorder, and more than 70% of people with a mental illness go untreated.

In the United States, researchers estimate that over 60 million Americans have a mental health condition; however, half of these people are not receiving treatment of any kind.

If this generation of young people lacks faith in counseling or other types of mental health treatment, it is not because effective treatments don’t exist. In 2012, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) published a resolution that recognized the general effectiveness of psychotherapy. Further, meta-analyses have shown that the average client receiving therapy is “better off” than 79% of untreated clients. Additionally, the Society of Clinical Psychology division of the APA maintains a list of evidence-based therapies backed by modest and strong supporting research, including randomized clinical trials. However, a lack of trust in the mental health system has led to less engagement with treatment, especially considering the level of vulnerability required to pursue services. There are many barriers to mental health treatment that have nothing to do with the quality or existence of treatment options. A better system is long overdue, and for this to happen, major change must occur, not only on a structural or institutional level, but also in our attitudes and willingness as a society to prioritize mental health.

Many people lack knowledge about how to identify features of a mental health condition or access treatment. Individuals are also hindered by internalized feelings of prejudice and expectation of discrimination. Together, these factors impair one’s ability to self-identify with an illness, which leads to difficulty in initiating treatment and contributes to increasingly negative attitudes towards receiving care.

Addressing Stigma

When an individual who is part of a marginalized population seeks mental healthcare, they risk experiencing discrimination or even violence from care providers. The compound effects of bearing multiple stigmatized labels makes accessing treatment even more difficult. Countless individuals experience discrimination or geographical, financial or cultural barriers to treatment.

But what happens when these barriers are removed? Even in high-income areas where providers are highly concentrated, community engagement is still low. What we find is that when money and accessibility are no longer an issue, stigma still remains, and stigma does not discriminate based on socioeconomic status.

Countless people, through no fault of their own, fall prey to stigmatizing beliefs about themselves and others, leading to a culture in which most people are wary, if not downright terrified, of accessing the mental healthcare system. Therefore, public health researchers should study and intervene on the stigmatization of mental health issues and treatment to improve accessibility on the individual level. If we began to treat mental health as a vital aspect of general health and well-being, we could advocate for improving accessibility through public education and policy.

Addressing stigma can combat the downstream issues of accessibility, affordability and discrimination people face across all domains of life. When our attitudes about mental health become benevolent, understanding and accepting, we can begin to promote new policies that will dramatically improve the quality of life for those who struggle. Mental health is a public health issue, and in applying a public health lens to reduce stigma, we begin to address the systems that makes treatment feel unapproachable in the first place. Many of us keep our pain to ourselves, but this experience is universal. In order to break down these barriers, the best thing we can do is to keep talking about it.

Pingback: Introducing Intervene Upstream: 2019 Inaugural Release » Intervene Upstream, the online peer-reviewed public health publication for graduate students